By Nelly Nyadzua My nature has always been looking out for the welfare of people. I can describe myself as very empathetic. Having the career change, going into cybersecurity with backing in artificial intelligence, is a very technical path. But I felt there is a way I can give back to the community, and not enclose the knowledge to myself. I have been training on matters of digital security and how people can guard themselves from bad actors online. That wasn’t enough. The more I worked on projects, building models and securing systems, I noticed that the policies and regulations in place are not actualized to protect the consumer. Well, you can say everyone is out the to make a profit or all. This is how I embarked on my journey to data privacy and protection. In my research, I swam into oceans of documents, articles and a very huge lingua, that as a techie…., well let’s say wasn’t favourable to a layman. On top of online research, I networked, asked questions, explained my shortcomings as I sought an interpretation of laws, and that’s how I learnt of Kenya Internet Governance (KeSIG) school convened by Kenya ICT Network (KICTANet). That was in 2018. All this time, I thought KeSIG was an add-on certification course for lawyers, ha ha (laughing emoji). One day, in 2021, a friend challenged me to look into KeSIG course content. It was more than what I thought. The school explained to students matters of internet governance affecting Kenya, Africa and privacy laws in various countries in the World ( EU GDPR, Canada, Brazil and other countries). I found it fascinating that the coverage extended beyond legal issues to include current trends in technology, artificial intelligence, and cybersecurity. I started attending the workshops held by KICTANet to sensitize citizens on digital policies and rights. In 2022, I applied to attend KeSIG and did not cut. Of course, I was heartbroken, but I didn’t lose hope. I continued to attend sensitization workshops and actively applied the skills I gained through training, advocacy on social media, and engaging with citizens. I also wrote articles on digital privacy and data governance. Additionally, I attended data privacy conferences, participated in the ISOC Kenya chapter, and joined ISACA this year. Fortunately for me, I applied for the 2023 intake and got selected! I am glad I worked on my end and talked to alumni of KeSIG in polishing my application. The classes came, WOW!!! They were intense. Talk about research! We had live classes, online module classes, class discussions and individual essays where you explained the daily topics in essays. The whole writing had me, but I came out victorious. We also had timed exams, that challenged our intellect. KeSIG is fire with a reason. I am grateful for how the faculty was always hands-on, ready to help, ready to explain and keep us in check with our daily deliverables. We also had industry key players coming to deliver sessions to us, and yes, we had to do articles on them, (smiley face). https://www.linkedin.com/posts/nelly-nyadzua_kesig-certificate-activity-7081642307090825216-Kjb9?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop I am fired up to churn out more content on advocacy on internet governance, confident in sitting and giving my opinions at tables that discuss internet governance in technology that affects me as a woman, a youth living in Africa. Today, I say thank you to all who made KeSIG 2023 a success, and if you are ever considering a starting point in internet governance, KeSIG is your step one. Nelly Nyadzua is a skilled and accomplished professional with a strong background in cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and cybersecurity. She is an AWS Cloud Practitioner and AI Graduate Student. She is also a Cybersecurity 2022 Fellow and KeSIG 2023 Fellow.

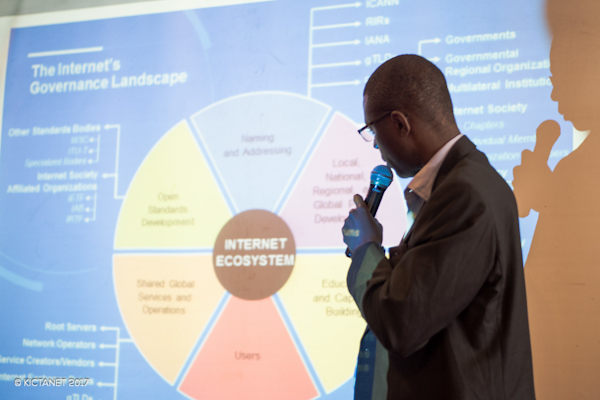

KeSIG Shaping Kenya’s Internet Governance Ecosystem Through Capacity Building

By Judy Muriuki As an avid participant in the Internet ecosystem, I was fortunate to be selected as a fellow for the 7th cohort of the Kenya School of Internet Governance (KeSIG). KeSIG is a flagship program by the Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet). It was the 3rd virtual edition comprising 118 participants from around the region with varied backgrounds, but all passionate about being part of the Internet Governance (IG) conversation. Through the expertise of the school’s management, presentations by industry experts and the self-paced learning system, I gained knowledge that helped me to appreciate the stakeholders within Kenya’s IG ecosystem. Beyond giving me a broader context of the roles played by actors, I got a better understanding of the contribution made by both the private sector and civil society towards the policy-making process. This contribution was made clear when the president rejected the ICT Practitioners Bill in late June and asked parliament to consider concerns raised by practitioners (Nderitu, 2022). The final two weeks of the KeSIG course became busy for me. I was completing the self-paced learning from both the KeSIG and the Internet Society (ISOC) where I had enrolled for Internet Governance courses. Doing the studies concurrently turned out to be a significant advantage for me, as I was able to contextualise and compare concepts within the global, regional and local perspectives. The conversations on WhatsApp and, the platform’s chat forum was eye-opening and motivated me to complete the readings, assignments and quizzes. By the time the Kenyan IGF, themed Resilient Internet for a shared sustainable and common future, was taking place on Thursday 30th June; I was conversant with the conversations having a good grasp of the issues, actors and policies being discussed. My biggest takeaways from this training were: I would recommend internet users enrol in this program to better understand and participate in the internet conversation. In 2016, the UN declared that it considers the internet to be a human right. This was with an addition being made to Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which states: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.” Section 32 adds “The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet” and another 15 recommendations that cover the rights of those who work in and rely on Internet access. It also applies to women, girls, and those heavily impacted by the digital divide. As the world moves socially, politically and economically online, internet users need to understand the internet’s environment to better participate and protect themselves, their data and their networks. To continue engaging in the IG conversation around Kenya and globally, facilitators encouraged us to visit the following stakeholder websites and engage with industry stakeholders. The suggested links are below: Judy Muriuki is a digital content creator passionate about using ICT to improve the quality of life for its users, especially in Africamarginaliseded communities. Follow the writer on LinkedIn. References Nderitu, S. W. (2022, June 21). President Uhuru Kenyatta Declines to Sign ICT Bill, Sends It Back to Parliament. Tech Trends Ke. Retrieved July 7, 2022, from https://techtrendske.co.ke/president-uhuru-kenyatta-declines-to-sign-ict-bill-sends-it-back-to-parliament/

7th Kenya School of Internet Governance Session Kicks Off

The Kenya School of Internet Governance (KeSIG) virtual sessions began Friday. KeSIG is one of the Kenya ICT Action Network’s (KICTANet) capacity building programs that aims to promote diversity and inclusion in the country’s ICT policy dialogues and beyond. The program responds to the need and importance of ensuring inclusive cyber policy. It was established in 2015 to bring in stakeholders from different backgrounds and expertise such as human rights, fintech, technologists and lawmakers to participate in Kenya ICT policy development. The KESIG course was designed to take place over three weeks. Students take the first two weeks to go through the online modules. The course covers introduction to internet governance, pathways to internet governance and participation in the internet governance processes. The third week is reserved for practical interaction with internet governance players such as ICANN, KENIC, human rights organizations, private sector and policy makers through industry presentations. The students are also expected to attend the Kenya Internet Governance Forum (KIGF). The 2022 Cohort The 2022 cohort was drawn from a pool of 331 applications. The call for participation was targeted to individuals across the country interested in ICT policy and regulations. 118 applicants were selected ensuring gender, stakeholder and regional balance: Females (62), male (54), preferred not to say (1) and other (1). In terms of sectors, within the civil society organisations (14), academia (23), private sector (53), public sector (20) and from the media. The cohort also enjoys participation from the east African Countries, Uganda and Tanzania. In Kenya, they are spread across 47 counties including Meru, Kilifi, Nairobi, Marsabit, Nyandarua, and Kisii among others. Since its inception, KeSIG has expanded the Kenyan ICT policy dialogue space, promoting inclusive policies and collaboration between stakeholders in the ICT sector. The KESIG alumni are now spread over, both in the global and National ICT policy fields. The training has enabled proactive policy interventions in digital rights, Internet access, and sector developments such as in the finance, agriculture and healthcare industries. This year’s KeSIG is being supported by Meta. KICTANet expresses huge gratitude for all the current and previous supporters. About KICTANet KICTANet is a multistakeholder think tank for Information and communications technology policy formulation whose work spans Stakeholder engagement, capacity building, research, and policy advocacy. The network was established to promote an enabling environment in the ICT sector that is robust, open, accessible, and rights-based through multistakeholder approaches.

Why Parliament must not pass the anti-pornography bill

By Winfred Gakii. Early 2021, Garissa Township MP Aden Duale tabled a bill to criminalize pornography. The Computer Misuse and Cybercrime (Amendment) Bill, 2021 was gazetted on 16th April 2021 and read for the first time on 9th June 2021. The bill seeks to amend the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, 2020, which is currently being challenged at the Court of Appeal as unconstitutional. In his presentation on the purpose of the bill, Duale states that the objective of the bill is to protect children from exposure to inappropriate sexual content. The Departmental Committee on Communication, Information and Innovation received two memoranda from the public participation call; one joint memorandum from civil societies, including ARTICLE 19 Eastern Africa and another one from the Communications Authority of Kenya. Both memoranda warned that the bill violates freedom of expression and by and large recommended deletion of the anti-pornography clauses and those that criminalize content that might cause people to commit suicide or join extreme religious or cult activities. The Committee on 4th August 2021 recommended the Bill for tabling in Parliament with only slight textual amendments, and recommendation for deletion of the anti-terrorism clause. This clause criminalizes the publication of electronic messages aimed at recruiting members of the public to terrorist activities and imposes a fine of up to twenty million and an imprisonment term of up to 25 years. A similar offence under Section 30A of the Prevention of Terrorism Act imposes a maximum imprisonment term of 14 years. The offence is improperly canvassed under the bill since it is already an offence in Kenya elsewhere. The clause also risks exposing individuals to excessive criminal liability since, with the same facts, one could be charged under both laws. The bill is currently ripe for second reading. The bill The Computer Misuse and Cybercrime (Amendment) Bill, 2021 introduces, among others, the offences of production, possession and publication of pornography through a computer system. It further criminalizes downloading, distributing, transmitting, disseminating, circulating, delivering, exhibiting, lending for gain, exchanging, barter, selling or offering for sale, letting on hire or offering to let on hire, offering in any way, or making available in any way from a telecommunications apparatus pornography. The bill also mandates the National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee to recommend some websites to be rendered inaccessible within the Republic of Kenya. It further prohibits the use of electronic media to promote terrorism, extreme religious or cult activities. The vague definition of pornography Every offence must be clearly defined to delineate prohibited conduct from benign actions. Additionally, the offence must be defined precisely to guide the courts in determining criminal cases before them; and the police in enforcing the law. Even more importantly, the clarity enables the public to regulate their conduct accordingly. Finally, a concise definition of offences ensures that legitimate conduct is not curtailed, especially when it comes to legitimate speech. Pornography is defined in the Computer Misuse and Cybercrime (Amendment) Bill to include any data, whether visual or audio, that depicts persons engaged in sexually explicit conduct. This definition is open to interpretation and police will have discretion on who to arrest and charge based on their individual interpretation of what constitutes ‘sexually explicit conduct. The phrase ‘sexually explicit’ is so subjective that it will lead to inconsistent application of the provision. The overbroad nature of its definition will open it up for abuse. Even more alarming is the clause that mandates the National Computer and Cybercrimes Coordination Committee to recommend websites to be rendered inaccessible. The Committee comprises mostly representatives from the security sector including internal security, Kenya Defence Forces, National Police Service, National Intelligence Service and Director of Public Prosecutions. There are no criteria established for determining what websites should be blocked. Related, there is the likelihood of recommending blockage of websites with legitimate content. This proposed procedure contravenes international law as content moderation practices by the government have to incorporate judicial oversight as a check. Removal of websites will interfere with the free flow of information online violating the right to freedom of expression and access to information. Privacy concerns The bill criminalizes both the demand and the supply of pornography. It prohibits content that adults can view in the privacy of their homes or gadgets. It also criminalizes the private sharing of pornographic content as well as possession. The enforcement of the provisions of the bill on the demand side will invariably violate the right to privacy. This is because efficient enforcement of the law will inevitably necessitate surveillance of the public’s communications and searches of their homes. Heavy censorship and surveillance of communications renege on the democratic promise of the 2010 Constitution. Punitive penalties The offences under the bill attract a penalty of up to KES 20 million or an imprisonment term of up to five years, or both. The penalty and the imprisonment term are extremely disproportionate given the conduct they seek to deter. Limitation of freedom of expression under the Constitution While freedom of expression is not an absolute right, its limitation must comply with the Constitutional criteria in place. Freedom of expression can only be limited under the Constitution of Kenya when it relates to propaganda for war; incitement to violence; hate speech; or advocacy of hatred that constitutes ethnic incitement, vilification of others or incitement to cause harm; or is discriminatory. There is also responsibility imposed on individuals that, in exercising freedom of expression, they shall respect the rights and reputation of others. Any limitation must be provided for in law, serve a legitimate aim and be necessary and proportional in a democratic state. What is the legitimate aim of prohibiting pornography? International law recognizes the protection of children as a legitimate ground for prohibiting pornography. The Convention on Cybercrime of the Council of Europe, otherwise known as the Budapest Convention, encourages states to criminalize the production, possession and distribution of child pornography. The African Union Convention on Cybersecurity and Personal Data Protection, which has not come into force yet, also

Kenya School of Internet Governance

Kenya School of Internet Governance (KeSIG) is in its seventh year in 2022. The very successful inaugural school was held in 2016 in Nairobi with 50 participants going through an intense three day training. Read more here. The school targets Kenyans from all sectors- government, academia, tech community and civil society who are new to Internet Governance issues. KeSIG is an introductory course covering technical, economic, legal and contemporary social issues brought about by the Internet and how they affect Kenyan decision making. It aims to build critical mass of individuals advocating for Internet rights and freedoms through equipping the participants with the skills needed to participate meaningfully in local, regional and global policy discourse. The 2022 KeSIG program The 2021 KeSIG program The 2020 KeSIG program The 2019 KeSIG program The 2018 KeSIG program The 2017 KeSIG program The 2016 KeSIG program Impact and past KeSIG fellows